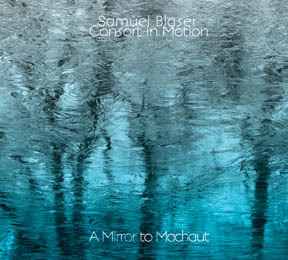

Samuel Blaser Consort in Motion

A Mirror to Machaut

SGL1604-2“Fearlessly modern, yet respectfully regal, Blaser’s adventurous arrangements and reinterpretations offer the best of both worlds…Consort in Motion is a high-water mark in the enduring lineage of the Third Stream.”

– Troy Collins, AllAboutJazz (reviewing the first Consort in Motion release)

#7 Rising Star on trombone in the 2013 Downbeat Critics Poll, Swiss trombonist Samuel Blaser’s star is rising internationally. In his early 30s, he has two acclaimed releases on Hatology with his current quartet, a new quintet on Fresh Sound co-led with bassist Michael Bates, a duo with drummer Pierre Favre, and a solo trombone record, among other projects. Though living in Berlin he is well known on the New York scene. Consort in Motion began in New York in December 2010 as a recording project for the Swiss label Kind of Blue. That record gained many raves, but Blaser was interested in touring. After Paul Motian died he decided to modify the personnel, retaining Russ Lossing on piano (plus, this time, Rhodes and Wurlitzer), bringing in Gerry Hemingway on drums and percussion and Drew Gress on bass, and adding a 2nd horn, Belgian reed player Joachim Badenhorst (co-leader of the trio Equilibrium, with two releases on Songlines). The concept remains that of blending early music forms and jazz improvisation, but where the first record focused on the early Italian baroque, this one finds inspiration in the the sophisticated court musics of Machaut and Dufay.

Blaser’s conservatory studies involved both classical music and jazz, and he was already familiar with the late medieval era. What interests him is how its formal elements – modes, melodies, structural and rhythmic devices, etc. – can be freely adapted in a creative music context into new pieces that require improvisers to come up with ‘solutions’ to the stylistic and expressive challenges they pose. But he is also quite fascinated in early music as a performer, and plays sackbut in a duo with Jay Elfenbein. This tension between homage and transformation, a continuum from rather faithful transcription to free arrangement to recomposition, gives A Mirror to Machaut both expectation and surprise – what will the next piece be like? It may sound nothing like the work it is based on, yet somehow a continuity of moods from track to track is established. Blaser’s notes offer pointers on what he’s up to, and Todd McComb of medieval.org provides a grand overview, but pleasure is solidly grounded first of all in the listening experience itself. Blaser comments: “A Mirror to Machaut is a vision, a suggestion of how Machaut’s and Dufay’s music can be used in improvised music. I might do something completely different tomorrow but this album reflects my current interests: from early music to contemporary music passing by improvised music, jazz and various grooves. However I don’t think I’ve forged any kind of new hybrid music here. I think the music sounds like mine but spiced with medieval colors.”

“I like to compose music that it’s possible to play with: explore the form, extend the speed of a melody, create somehow complex forms with ‘easy’ material…The methods used to create jazz pieces on A Mirror to Machaut are very similar to what I did in the first album. However, I attempted to include more medieval elements such as isorhythms (Cantus planus, Hymn and Linea), hemiolas (Saltarello and Hymn), and simple counterpoint (Hymn). Emotionally speaking I think we were able to re-create the world of Machaut’s love songs with tunes like Bohemia, Hymn, Douce Dame, De Fortune and Complainte. Those melodies are extremely beautiful and some of them were easy to put in a jazz context…On Colors we were able to almost get a Milesian vibe… I also attach a lot of importance to the search for sounds, space, and interactions between the musicians… I do find a lot of similarities between the two worlds: the ways of shaping the music and of phrasing lines are almost identical. The variety of articulations, dynamics, rhythmical cells, the delicacy and the lightness in early music is incredibly rich and can easily be translated to improvised music.”

With an expanded instrumental palette, the textures and colours are often scintillating, though with all the freedom and exuberance of the playing there is still a sense of reserve, elegance, at times almost of austerity. Blaser treats medieval music not as exotic fusion fodder but as a comprehensible world that casts its long spell across the centuries. He was aided in the final shaping of the arrangements by producer Benoît Delbecq, who was also hands-on during the recording and post-production process and obtained superb sound quality. (Not co-incidentally they are both members of clarinetist’s François Houle’s 5+1 Ensemble on Songlines.)

Watch the excellent “making of” video here.